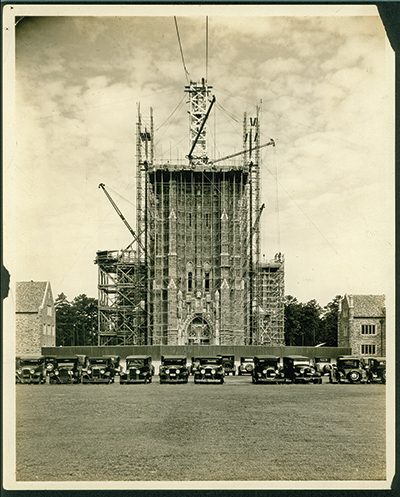

On Oct. 22, 1930, the foundation of Duke's signature building was laid on ground that before was nothing but serene, undeveloped forest.

The spot would host a structure to dominate all surrounding buildings. "A great towering church," is what James B. Duke wanted, and with its dedication in 1935, a 210-foot tall chapel is what he got: the centerpiece of Duke's campus.

In a twist of fate, the legacy of that construction and Duke's desire for an English Gothic building uniquely placed in central North Carolina has led to today's evolving campus. As Duke prepares to close Duke Chapel on May 11 for about a year of restoration, James B. Duke's tastes in architectural style from more than 80 years ago provides an almost literal blueprint for an $18-million project to rehabilitate the Chapel's limestone ceiling and replace its original roof.

"In 1930, designers mis-estimated by a matter of millimeters how limestone would change over its lifetime, and the Chapel has never had any serious restoration work," said Tallman Trask III, Duke's executive vice president. "Now it's time to clean things up, but when we're done, there won't be a noticeable difference to the architectural style."

In his 1939 book "The Architecture of Duke University," former Duke English professor William Maxwell Blackburn wrote about the rarity of the decision by Duke to build a Gothic chapel in lieu of more modern construction designs. Specifically, Blackburn noted the principles of architecture started by builders of the Middle Ages would be similarly used at Duke, where Duke Chapel's vaulted ceiling would balance pressure of its towering walls through arced limestone ribs that come together like a wishbone.

"The ceiling of the nave is an example of one of the most complicated types, the pointed, ribbed vault," Blackburn wrote, calling the process "the major structural difficulty" of original construction. To create a style of building requested by James B. Duke, however, the ribs would be necessary as a distinguishing mark of the Gothic style.

However, that commitment to construct the Chapel in a traditional fashion meant the building would eventually need a modern restoration to preserve the historic space.

Clay tile between the limestone ribs in the ceiling has aged, slowly absorbing moisture over the decades. As the tiles take in moisture from the air, they expand in their wishbone design, shifting pressure and creating a need for restoration.

"In addition, the mortar used between the limestone ribs is very brittle and doesn't compress, so it can't transfer the structural load like a newer, flexible mortar would," said Paul Manning, director of Duke's Office of Project Management. "So right now as two of these ribs slowly come together, they begin to reduce the mortar to powder."

In its short lifespan, the Chapel's design has come full circle. The uniqueness of its original design is now the reason Duke will go back to work for the first major restoration in the Chapel's history.

While never performed before at Duke Chapel, a restoration of this kind isn't uncommon. In 2008, Prague's St. Vitus Cathedral underwent similar repair and the Cathedral Notre Dame in Rouen, France, has also restored cracked mortar.

The restoration process may feel routine to the structural engineers, materials scientists and architects handling the work. Illinois-based Wiss, Janney, Elstner Associates, Inc., which is handling the Chapel restoration, specializes in repair of historic structures, and in recent years restored the Washington Monument and National Cathedral.

Duke's restoration follows a review in 2012 in which engineers performed a hands-on inspection of about 95 percent of the ceiling's surface. Once renovation work begins at Duke Chapel in May, engineers will carefully grind brittle mortar away - 3/8 of an inch between each rib - and replace it with new, more flexible material.

One issue to address during the work will be the amount of fine dust created in the process of grinding old mortar. Facilities staff have likened the amount of dust created to something akin to a snowfall. To address the issue, tent-like, popup structures will be used in areas of restoration, along with vacuums to suck up dust.

Some powder will get loose, so unattached objects like pews or podiums will be moved to a storage space during the project. Pieces of the Chapel's organs, which are permanently installed, will be sealed to keep dust out.

"We'll essentially build boxes around the pipes, then shrink-wrap them," Manning said. "It'll be like they're hermetically sealed."

While the ceiling involves about a quarter of the restoration - much work is dedicated to preparation and clean up - Duke will use the yearlong closure to do other work.

Nine stained glass windows will have their glass pieces removed and cleaned while lead caning is repaired and Red Oak wood molding in the building's chancel and transepts will be reconditioned. Outside, scaffolding will be constructed so crews can replace the Chapel's original roof, which is covered with lead-coated copper. Like other roofing projects at Duke, replacement copper tiles will go through an aesthetic treatment to keep the same appearance.

"When all is said and done, the best outcome for this project will be that nobody can tell what we did - inside or out," Manning said.

Since Duke Chapel's main worship space will be closed during restoration, administrators have made plans to move weekly services and special events to other locations. Sunday services will be in Baldwin Auditorium over the summer and in Page Auditorium for the 2015-16 academic year. This year's Christmas Eve service and the 2016 Easter service will move to Cameron Indoor Stadium.

It's a necessary change welcomed by Ned Arnett, R. J. Reynolds Professor Emeritus of Chemistry, who started attending services at the Chapel with his wife, Sylvia, in 1985.

Arnett said he always hoped the building wouldn't go the way of some cathedrals in Europe, which transitioned to museums, losing their original purpose along the way. He added that he's glad the upcoming restoration will allow for continued use of Duke Chapel for events and Sunday services after work is finished.

"The test of any civilization is its maintenance, and this magnificent building plays a great role in our community," Arnett said. "It's a minor dislocation to see that coming generations will be able to worship there."

Added Sylvia, "There's an inclusiveness with our community and all the visitors that come to the Chapel that won't be lost."

That's an important goal for the Rev. Luke Powery, dean of Duke Chapel. He said that even though work on the Chapel would shift gatherings to spaces across campus and Durham, it will allow for greater integration into the community at-large.

The restoration excites Powery in all sorts of ways, including the ability to hold services in new locations. Most notably, he looks forward to hosting "Christmas in Cameron" as part of Christmas Eve services in Duke's other historic building - Cameron Indoor Stadium. Above all, he said it's a privilege to be a part of this moment in Duke's evolution, which will pay dividends for decades to come.

"The chapel is closed for renovations, but remains open to God," Powery said. "The restoration is an opportunity to demonstrate the Chapel's mission as a great, loving church for the Duke and Durham communities, as well as to focus on all the people who make our congregation more than a building."

Designer

Julian Abele from the architectural firm of Horace Trumbauer of Philadelphia

Architectural style

Neo-Gothic architecture in the English style

Groundbreaking

Oct. 22, 1930

Dedication

June 2, 1935

Cost in 1932

$2.2 million

Height from foundation to spire

210 feet

Stained glass windows

77, depicting every major scene in the Bible

Insurance cost for windows in 1930

$200,000

Cost of cut stone for construction in 1932

$626,000

Organs in place

Flentrop (nave), Aeolian (chancel) and Brombaugh (Memorial Chapel)

By Bryan Roth, Duke University Office of Communication Services.